Best Things to buy from Khan el Khalili Bazar

September 29, 2025

A Local’s Guide to Navigating Khan el-Khalili Bazaar Without Getting Lost

October 30, 2025The history of Khan el Khalili weaves a captivating tale of trade, culture, and transformation in the heart of Cairo, Egypt. As one of the world’s oldest and most vibrant bazaars, Khan el Khalili has stood the test of time, evolving from a medieval caravanserai into a bustling hub that attracts millions of visitors annually. This legendary souk, nestled in the historic Islamic Cairo district, offers more than just shopping—it’s a living museum where the echoes of ancient merchants still resonate through its labyrinthine alleys. In this article, we’ll delve deep into the history of Khan el Khalili, exploring its origins, key developments, and enduring legacy, while highlighting why it remains an essential part of Egypt’s cultural heritage.

Origins in the Fatimid Era: The Foundations of a Trading Hub

To truly understand the history of Khan el Khalili, we must journey back to the Fatimid Caliphate, which founded Cairo in 969 CE. The site where the bazaar now stands was originally part of the eastern Fatimid palace complex, a restricted area reserved for the caliphs, their families, and officials. This included the burial grounds known as Turbat az-Za’faraan (the Saffron Tomb), where Fatimid rulers were interred, and a smaller palace called al-Qasr al-Nafi’i. During this period, Cairo functioned as an exclusive palace-city, largely closed off to common folk and focused on royal affairs rather than commerce.

However, subtle shifts began in the late Fatimid era. Viziers like Badr al-Jamali (r. 1087–1092) and al-Ma’mun al-Bata’ihi (r. 1121–1125) started integrating economic elements by establishing a mint (Dar al-Darb) and a customs house (Dar al-Wikala) near what would later become significant landmarks. These initiatives marked the first introduction of foreign trade into the city’s core, setting the stage for Khan el Khalili’s future as a commercial powerhouse. Although trade was limited, these early developments planted the seeds for the bazaar’s transformation, blending royal prestige with emerging mercantile activities.

As the Fatimid dynasty waned, the area began to open up. The decline of the nearby port city of Fustat further elevated Cairo’s role in regional trade, drawing merchants and travelers inward. This period in the history of Khan el Khalili highlights how political changes inadvertently fostered economic growth, turning a sacred burial site into a precursor of one of the Middle East’s most famous markets.

The Rise During the Mamluk Period: Birth of the Bazaar

The true birth of Khan el Khalili as we know it occurred in the 14th century under Mamluk rule, a golden age for Cairo’s architectural and commercial expansion. In 1382, during the reign of Sultan Barquq, Emir Jaharkas al-Khalili—a high-ranking official serving as the Master of Stables—demolished the Fatimid mausoleum to construct a grand caravanserai. This structure, named after its founder, was designed to accommodate merchants and their goods, featuring a central courtyard for storage and trade. The demolition was controversial; legend has it that the bones of the Fatimid caliphs were unceremoniously discarded in nearby rubbish heaps.

Initially called Souq al-Juma (Friday Market), the bazaar quickly became a vital center for international commerce. The Mamluks, known for their patronage of architecture and trade, encouraged the development of fixed stone buildings over temporary stalls, making taxation and regulation easier. By the late 14th century, additional khans (inns) and wikalas (warehouses) sprouted around the original structure, including the Rab’ al-Badistan by Amir Yashbak min Mahdi and the Wikala of Sultan Qaytbay near al-Azhar Mosque.

This era in the history of Khan el Khalili saw the bazaar flourish as a hub for exotic goods like spices, precious stones, slaves, and textiles. Merchants from across the Middle East, Africa, and Europe converged here, turning the district into Cairo’s economic epicenter. The integration of waqf (charitable endowments) systems further fueled growth, as revenues from shops funded nearby religious institutions like madrasas and mosques. Architecturally, the Mamluk influence is evident in the multi-storied buildings with ornate facades, courtyards, and street-level shops, many of which still define the bazaar’s layout today.

Redevelopment and Peak in the Late Mamluk Era

By the early 16th century, under Sultan al-Ghuri—the last effective Mamluk ruler—the bazaar underwent significant redevelopment. In 1511, al-Ghuri demolished parts of the original khan to build the Wikala al-Qutn (also known as Khan al-Fisqiya) and introduced monumental stone gates, such as Bab al-Badistan and Bab al-Ghuri, which survive to this day. He aimed to create a more organized grid-like plan, possibly inspired by Ottoman bedestens (secure markets for valuables), enhancing security for high-value trades.

This phase marked the peak of Khan el Khalili’s Mamluk-era prosperity, with over 20 interconnected khans and souqs by the early 16th century. The bazaar became synonymous with luxury goods, attracting traders from distant lands and solidifying Cairo’s position in global trade networks. The history of Khan el Khalili during this time reflects the Mamluks’ vision of blending commerce with Islamic architecture, creating a space that was both functional and aesthetically magnificent.

Ottoman Influence and Evolution: Adaptation Through Centuries

Following the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517, Khan el Khalili adapted to new rulers while retaining its core identity. The bazaar became closely associated with Turkish merchants, who occupied structures like the Wikala al-Qutn. Prosperity ebbed and flowed with political stability, but the district remained a key node in Ottoman trade routes, dealing in spices, cotton, and jewelry.

The 17th and 18th centuries saw restorations and new constructions, including the Wikala of Sulayman Agha al-Silahdar in 1837, which replaced a ruined Mamluk khan. By the late 18th century, nearly 40 khans existed in the area. The 19th century brought modernization, with Al-Muski Street cutting through the bazaar, improving accessibility but altering its medieval charm. In the 20th century, residential blocs were added in the 1930s by Princess Shawikar, blending old and new.

Despite challenges, including terrorist attacks in 2005 and 2009 that temporarily impacted tourism, the bazaar endured. Its designation as part of UNESCO’s Historic Cairo World Heritage Site in 1979 underscores its global importance.

Modern History and Preservation: A Living Legacy

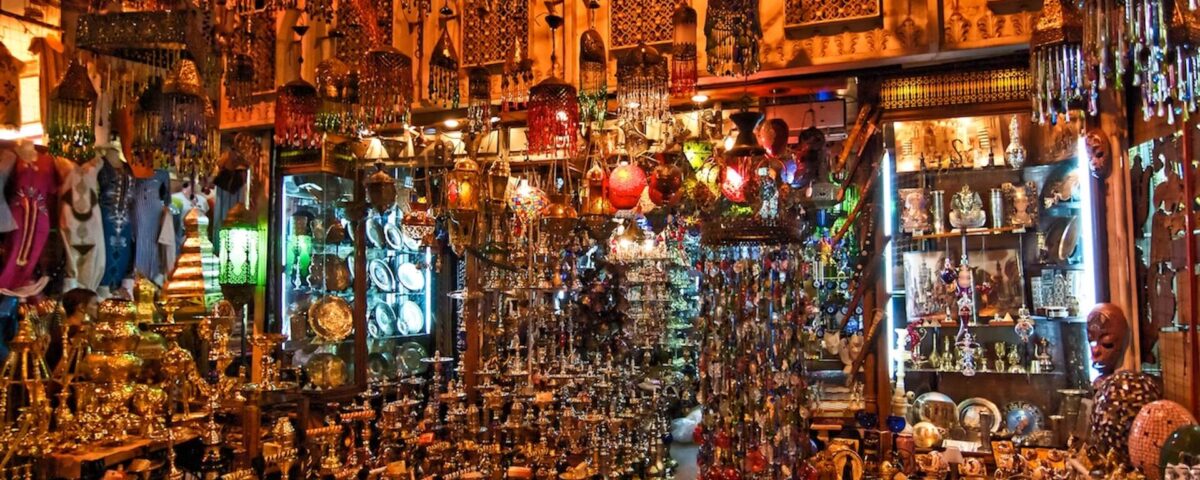

In contemporary times, the history of Khan el Khalili continues to evolve as a tourist magnet and cultural icon. Renovations in the 20th and 21st centuries have preserved its Mamluk architecture while adapting to modern needs. Today, the bazaar spans a vast area bounded by al-Muizz Street, al-Muski Street, and the al-Hussein Mosque, offering everything from gold jewelry and spices to handmade crafts.

Artisan workshops keep traditional crafts alive, and historic cafes like El-Fishawy (established in 1773) provide a taste of old Cairo with Arabic coffee and shisha. The bazaar’s cultural significance extends to literature, inspiring works like Naguib Mahfouz’s Midaq Alley and P. Djeli Clark’s The Angel of Khan el-Khalili. Efforts by Egyptian authorities and UNESCO ensure its preservation, balancing heritage with the demands of a global audience.

Cultural and Economic Significance: Why Khan el Khalili Endures

Throughout the history of Khan el Khalili, its role as a cultural and economic bridge has been paramount. From Mamluk trade in precious stones to today’s souvenir markets, it has mirrored Egypt’s socio-economic shifts. The bazaar fosters community, with distinct sections for goldsmiths, coppersmiths, and spice vendors, each preserving age-old traditions. Economically, it supports thousands of artisans and vendors, contributing to Cairo’s tourism industry. Culturally, it embodies the spirit of Islamic Cairo, where history, faith, and commerce intertwine seamlessly.

FAQs

What is the origin of the name “Khan el Khalili”?

The name derives from Emir Jaharkas al-Khalili, who built the original caravanserai in the 14th century during the Mamluk era.

How old is Khan el Khalili?

Trading at the site dates back to the 14th century, making it over 600 years old, though its roots trace to Fatimid times in the 10th century.

What architectural features define Khan el Khalili?

It features Mamluk-style gates like Bab al-Badistan, courtyards in wikalas, and ornate facades, blending functionality with Islamic artistry.

Has Khan el Khalili faced any modern challenges?

Yes, terrorist attacks in 2005 and 2009 affected tourism, but the bazaar has rebounded as a resilient symbol of Cairo’s heritage.

Why is Khan el Khalili important today?

It preserves traditional crafts, supports local economy, and offers a glimpse into Egypt’s rich history, attracting global visitors.

Final Words

The history of Khan el Khalili is a testament to Cairo’s enduring vibrancy, where centuries of trade and culture converge in a mesmerizing tapestry. From its Fatimid origins to its modern-day allure, this bazaar invites us to explore not just its alleys, but the soul of Egypt itself. Whether you’re a history buff or a curious traveler, Khan el Khalili promises an unforgettable journey through time. Plan your visit and immerse yourself in this timeless wonder—it’s more than a market; it’s history alive.